Street Art and VARA: The Intersection of Copyright and Real Estate

May 2016 – Art & AdvocacyWhen New York real estate developers finally demolished the crumbling “5Pointz” water meter factory building and its 20-year-old graffiti wall in Queens, NY, in mid-2014, it brought an end to what had become a popular stop for tourists and local art buffs alike. Having purchased the property with the intent to put up a high-rise residential development, eventual destruction of the old factory and its graffiti art wall by the developers was inevitable. Alteration of the graffiti art began in 2013 when the wall was whitewashed over by the developers on the eve of a preliminary injunction hearing before a New York federal district court in a case brought by a group of aerosol artists under the Visual Artists Rights Act, or VARA (Section 106A of the U.S. Copyright Act).[1] Real estate owners and developers need to take heed of VARA and the artworks affixed to their property, lest they find themselves in court.

5Pointz and Street Art

Over the course of nearly two decades, some 1,500 graffiti and street artists adorned the abandoned 5Pointz factory with colorful murals and “tag” flourishes that became a major tourist attraction. Known as the “Aerosol Art Center,” the artists had long-time permission from the property owner to paint the abandoned building’s façade, with only some restrictions on the type of street art so as to keep it in good taste. In 1993, developer Gerald Wolkoff gave the named plaintiff, Jonathan Cohen (a/k/a “Meres One”), authority to be curator of the art and the keys for access to spaces to work and store supplies on the 5Pointz property. But plans to demolish the property to make room for the residential project later emerged, and the New York City Landmarks Commission denied preservation protection. Cohen and a group of the artists filed suit in the fall of 2013 seeking injunctive relief, alleging that the proposed destruction of the art would be a violation of VARA, which provides qualified protections to the author of a work of visual art to “prevent any destruction of a work of recognized stature….” A second prong of VARA under Section 106A prevents the “intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to [an author’s] honor or reputation….”

http://clancco.com/wp/2013/11/vara-moral-rights-pa...

Apart from much of the art having been whitewashed over the night before, the court declined to grant a preliminary injunction. While characterizing the Aerosol Art Center as a “repository of the largest collection of exterior aerosol art (often also referred to as ‘graffiti art’) in the United States,” the court ruled on November 20, 2013, that denial of relief under VARA was warranted because of the “transient nature” of the graffiti based on the artists’ knowledge that the building eventually would be demolished, as well as the availability of monetary relief for damages (which generally precludes the right to injunctive relief). The case was still kept alive for ultimate trial, however, with the court noting that the issue of “recognized stature,” which is not a defined term under VARA, was best determined at the trial stage.[2]

In June 2015, however, nine of these street artists filed a new lawsuit against the developer, this time only for money and punitive damages under the second prong of VARA that protects against “mutilation” of art. The new claim was tied to the whitewashing of the 5Pointz graffiti wall, which the artists alleged was “entirely gratuitous and unnecessary,” “crude,” “unprofessional,” and designed to inflict “maximum indignity and shame to plaintiffs.” Unlike the burden the artist-plaintiffs have in the earlier filed case, which requires proof of “recognized stature” and focuses on destruction of a protected work, the relevant provision of VARA in the 2015 case avoids that burden and instead requires proof that the distortion and mutilation of the art were prejudicial to the artists’ “honor or reputation.” The plaintiffs allege such harm, as well as “humiliation, mental anguish, embarrassment, stress and anxiety, loss of self-esteem, self- confidence, personal dignity, shock, emotional distress, inconvenience, emotion pain [sic] and suffering and any other physical and mental injuries Plaintiffs suffered due to Defendants improper conduct pursuant to VARA and the common law.”[3] The case remains pending.

Despite its demise, 5Pointz has helped propel street art into the limelight as a true art form that deserves protection. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and others cut their teeth on street art, and their works have skyrocketed in value, as have works by prominent street artists like Banksy. Still, most street artists earn meager livings and never see a dime from their art. But that too is changing. Recently, street artists have become more aggressive in bringing copyright infringement actions against companies that have co-opted their art for use in advertising campaigns and other commercial uses.

For example, in January 2016, a group of Miami street artists sued celebrity pastor Rich Wilkerson in Miami federal court for copyright infringement for using their street art murals without permission to advertise and promote his new church spinoff.[4] In 2014, famed Miami street artist David Anasagasti (aka “Ahol Sniffs Glue”), whose murals were commissioned and thus legally created, sued American Eagle Outfitters in New York federal court for copyright infringement for using his iconic “droopy eyeball” motif in a global advertising program; the case settled fairly quickly.[5]

http://www.aholsniffsglue.com/gallery/walls/

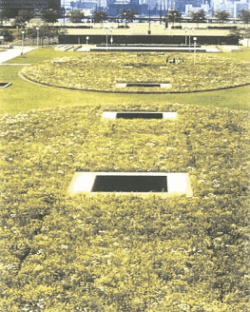

Recently, muralist Katherine Craig sued a real estate developer, Princeton Enterprises, after it allegedly threatened to destroy or mutilate an iconic 100-by-125 foot watercolor mural painted by Craig in 2009 on a nine-story building wall in Detroit and dubbed “The Illuminated Mural.” The developer has been considering redevelopment of the building for multifamily housing. Craig’s complaint, which was filed in January 2016 in Michigan federal court, alleges the work is protected by VARA and seeks to enjoin its destruction or mutilation during her lifetime. The work has become a notable landmark in downtown Detroit and has been cited by the Detroit Free Press as a “drop-dead gorgeous mural.” Craig has received many accolades over the mural, including a grant by JP Morgan Chase Foundation to create another mural in the same area, and Craig’s reputation has grown significantly since. [6]

(From the Complaint)

Craig had received permission to paint the mural from the building’s prior owner, Boydell Development Co., which later sold the property in 2012 to an intermediate owner who then resold it in 2015 to Princeton Enterprises.[7] According to the complaint, Craig signed an agreement with Boydell that the mural would “remain on the building for no less than a 10 year time period,” and Craig never agreed to waive her lifetime rights of attribution and integrity under VARA. She registered her copyright in the mural in 2012. How this case will play out is uncertain, and it may be entirely premature because the developer, as of the time of this article, had not yet made a final decision on how the property would be developed.

VARA and the Copyright Laws

With all this attention and litigation, real estate owners and developers—particularly those in urban areas—need to understand the legal underpinnings of VARA and related copyright principles as applied to street art. Unlike traditional copyright protection, which guards against unauthorized copyright and exploitation without the copyright owner’s consent, VARA is intended to protect the attribution of an artist and the integrity of a protected work, also known as the droit moral, or moral rights of the artist. Such moral rights, while long a part of European jurisprudence and culture, have not historically been a part of U.S. law.

VARA codifies two distinct “moral” rights, protecting artists from (i) the intentional or “grossly negligent” destruction of a work of “recognized stature,” and (ii) the intentional distortion, mutilation or other distortion of a work that would be prejudicial to the artist’s “honor or reputation.”[8] Changes due to the passage of time or decay of materials, however, as well as modifications for conservation or public presentation that are not done in a grossly negligent manner, are recognized exceptions to these protections.

VARA defines a covered “work of visual art” narrowly as limited to a “painting, drawing, print, or sculpture” and a “still photographic image produced for exhibition purposes only.” Whether a particular work falls within this definition “’should not depend on the medium or materials used,’ since ‘[a]rtists may work in a variety of media, and use any number of materials in creating their work.’”[9] Excluded from VARA coverage are “any poster, map, globe, chart, technical drawing, diagram, model, applied art, motion picture or other audio-visual work.” This is a much narrower definition than the Copyright Act’s general statutory protection for “original works of authorship,” which broadly include “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works.”[10]

VARA applies to applicable works created after its June 1, 1991 effective date; however, it also applies to works created before that date if title to the works had not, as of that effective date, been transferred from the author. Unlike the copyright in other works of authorship, VARA rights end when the artist dies. Available remedies under VARA include injunctive relief, monetary damages, defendant’s profits, statutory damages and, in the court’s discretion, legal fees. A copyright registration is not required to bring a VARA action or to secure statutory damages and legal fees, whereas a registration is required to sue for infringement and to seek statutory damages and legal fees for copyright infringement generally.[11] Significantly for property owners, VARA rights can be waived by a written document that specifically identifies the work and the uses of that work to which the waiver applies. This waiver is most important to real estate owners and developers, especially where permission is granted to street artists, as it was initially in the 5Pointz case.

The artist must also be the “author” of the work to qualify for copyright, and therefore VARA, protection. Even if an artist creates an original work, the artist will not be deemed the “author,” and therefore the owner of the copyright, if the work is a “work made for hire.” A work made for hire is one specially commissioned “for use as a contribution to a collective work…,” and the commissioning party, not the artist, is then deemed to be both the author from inception and the copyright claimant. But unless the specific art is intended to be part of a collective work comprised of multiple artists’ work product, such as may be argued for 5Pointz, it cannot qualify as a work made for hire.[12]

To be covered by VARA, a work of visual art must also be protected by copyright. Thus, works must be original and “fixed in any tangible medium of expression … from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated….”[13] Under the Copyright Act, a work is fixed “when its embodiment in a copy …. by or under the authority of the author, is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.”[14]

While the bar for “originality” is quite low, the Copyright Act excludes from protection certain basic elements, including the following: “Words and short phrases such as names, titles, and slogans; familiar symbols or designs; mere variations of typographic ornamentation, lettering or coloring….”[15] It is therefore arguable that a graffiti artist’s “tag” (e.g., “Smithy 129”) by itself is simply a “name” and number that does not have sufficient originality, even if it is displayed with an ornamental font or flourish. No reported decision has yet addressed that question.

What constitutes “transitory duration,” however, is not always clear. With respect to works of visual art, the Copyright Office takes the general position that for registration purposes “the Office cannot register a work created in a medium that is not intended to exist for more than a transitory period, or in a medium that is constantly changing.”[16] Unlike the broad scope of originality, the concept of “fixation” can get muddied when works are intended, either by their nature or by design, to be temporary. For example, Christo’s open space wrappings and flag installations, while unquestionably works of art, are intended to be fleeting. Christo claims copyright in those designs, but also permanently “fixes” the image through numerous physical drawings and photographs.[17]

A highly publicized attempt by a landscape artist to obtain redress under VARA against the Chicago Park District for its reconfiguration of the open space “Wildflower Works” wildflower garden he had created floundered before the federal Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. In a 2011 decision, the court held that the garden was not sufficiently “fixed” to warrant copyright protection because the shape and design of the garden changed over time due to its organic nature.[18] After accepting the position of the arts community that the garden could be classified as a work of postmodern conceptual art, the court stated: “The real impediment to copyright here is not that Wildflower Works fails the test for originality (understood as ‘not copied’ and ‘possessing some creativity’), but that a living garden lacks the kind of authorship and stable fixation normally required to support copyright….”[19]

(From the Seventh Circuit’s opinion)

For street art affixed to buildings, it would seem logical that the “fixation” requirement is met, but like the wildflower garden, this may depend on various factors. Is graffiti art merely temporary so as not to be “fixed” because it’s affected by natural elements, as was the wildflower garden landscape? Or, because it can be sprayed over by others, is there an expectation that it will be destroyed? Despite a paucity of caselaw on the issue, it would seem that fixation arguably has occurred at least when the materials used are intended to be long-lasting or permanent (such as enamel-based aerosols) and there are no imminent plans for demolition of the property. This would contrast, for example, with pavement chalk art, which disappears with the first rain, despite some mind-blowing creations by renown 3D chalk pavement artists like Julian Beever, who wisely photograph every step of their creations and publish books and websites so as to “fix” the works for copyright purposes.

www.julianbeever.net/index.php?option=com_phocagal...

In VARA cases involving destruction of a work of visual art, the key issue is what constitutes a “work of recognized stature,” which is a required finding for protection. The term “recognized stature” is not defined in VARA. A leading case on this issue is Carter v. Helmsley-Spear, which involved VARA claims for both destruction and modification to artists’ “walk-through sculpture” ceiling installations. After hearing art expert testimony (including from the president of the Municipal Art Society of New York), the federal district court held, in a case of first impression, that to establish “recognized stature,” a work had to be “meritorious” and have its merit recognized by “art experts, other members of the artistic community, or by some cross-section of society.”[20] While the district court found the work to qualify as one of “recognized stature” and protected by VARA, the Second Circuit reversed, finding the work to be a work-made-for hire, thus depriving the artists of any claim of copyright authorship under VARA. The Second Circuit did not address the “recognized stature” issue.

As the court noted in the 5Pointz case, only a handful of cases since the district court’s opinion in Carter have addressed the “recognized stature” issue. One New York case rejected “recognized stature” where the work, while meritorious, was created “solely as a display piece for a one-time event.”[21] Another case refused protection because the work had been commissioned for placement in the defendants’ private yard, which was obscured by hedges from public view, thus precluding recognition.[22] The 5Pointz court left open the question of “recognized stature” for trial, and cautioned that “defendants are exposed to potentially significant monetary damages if it is ultimately determined after trial that the plaintiffs’ works were of ‘recognized stature.’”[23]

In denying preliminary injunctive relief, which requires a showing of irreparable harm, the 5Pointz court cited “the transient nature of the plaintiffs’ works” based on evidence that while the lead artist-plaintiff believed the “24 works in issue were to be permanently displayed on the buildings, he always knew that the buildings were coming down—and that his paintings, as well as the others which he allowed to be placed on the walls, would be destroyed.” Nevertheless, with respect to the potential for money damages, the court held that “VARA protects even temporary works from destruction…,” thus implicitly acknowledging they were sufficiently “fixed” for copyright purposes.[24] This sets up an inherent contradiction: If the works qualified for any VARA protection—including money damages—they must be copyrightable and thus meet the “fixation” test. By sending the case to trial, the court implied copyrightability, although defendants could still challenge that. A work cannot be “transient” for copyright purposes at the preliminary injunction stage but otherwise sufficiently fixed and not transitory for substantive copyright purposes.

Lurking underneath street art that is affixed to buildings without permission of the property owner or lessee, is the illegality of the art itself under trespass and similar laws that protect property rights. For example, in New York graffiti is a Class “A” misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in jail. Illegal graffiti in New York is defined as any “etching, painting, covering, drawing upon or otherwise placing of a mark upon public or private property with intent to damage such property … without the express permission of the owner or operator of said property.”[25]

Does illegality itself vitiate copyright protection? The Copyright Act itself does not condition copyrightability on the legality of the manner of its creation or “fixation.” There is a compelling argument that copyright, and therefore VARA, protections extend even to illegal street art because copyright focuses on the original work that is created and not the manner of its creation. But even if a valid copyright claim is brought, courts have discretion in fashioning remedies that factor in equitable principles, and illegality would almost certainly be a factor. Indeed, because injunctive relief, such as to stop destruction of a building street art wall, is an equitable remedy, illegality would be an expected defense for a building owner, but may be insufficient to block a money damages award. At least one court has expressed the view, without deciding the issue, that graffiti art in a copyright case “would require a determination of the legality of the circumstances under which the mural was created.”[26] As a practical matter, most illegal street artists, who typically use pseudonyms, will not risk revealing themselves and facing potential prosecution.

Another key element of VARA is an exception for works that were installed in a building either before 1990 with the author’s consent, or after 1990 with an agreement between the author and building owner waiving the author’s VARA rights.[27] In those cases, if the art can be removed without its destruction, distortion, mutilation, or other modification, and the owner notifies or makes a good-faith effort to provide written notice to the author—who has an implicit obligation to maintain a current address of record (the Copyright Office provides a special Visual Arts Registry for this purpose)—the author then has 90 days to remove the art or pay for its removal, in which case the artist also reclaims title to the work.[28] Statements by building owners are also recordable to establish a record of attempts to contact an author.

Pointers for Real Property Owners and Developers

From a property owner’s perspective, here are some pointers to bear in mind:

- If you grant permission to an artist to affix art to your property, make sure there is a written agreement under which the artist waives his or her VARA rights, perhaps with certain conditions, such as an incentive payment to the artist if the work needs to be destroyed or altered for development or renovation purposes, relocation of the art if possible without destruction (subject to the artist’s statutory right to receive 90-days’ advance notice), or preservation of the art with high-resolution photography that could be printed and displayed elsewhere on the property.

- If you are acquiring a property with affixed visual art that could be protected, make sure your due diligence includes VARA-related issues. If the prior owner gave consent to the installation without any paperwork or waiver from the artist and a new project will require destruction or alteration, then consider an escrow to cover a potential claim by the artist. Alternatively, if the work is high profile and has gotten a lot of press, so as to potentially quality it as a work of “recognized stature,” try to cut a reasonable deal with the artist in advance of closing if the prospect of potential injunctive relief is real and any meaningful delay in construction would be costly.

- If a developer is acquiring property covered with street art that was illegally created, the likelihood of a VARA claim being made is more remote. As the issue of legality is not settled in the courts, however, owners should still assess whether the graffiti is protected by copyright as a work of visual art, which would likely require more originality than common street “tags,” and if it is of “recognized stature.” Indeed, if such art were a work by Banksy, it would raise these significant issues.

- Similarly, if legally created street art needs to be destroyed, consider if it is a work of “recognized stature.” Most street art will likely not meet this definition, although there are prominent potential examples like 5Pointz and Katherine Craig’s mural. Nevertheless, this remains a gray area in the law that can lead to protracted litigation and the need for experts, with an uncertain outcome. Do the research and consult confidentially with experts to make this assessment.

- Manage the press and your public image, if it matters. Local communities can become vociferous opponents of a development project if they oppose it or don’t like the developer where special permits or zoning variances are required. If the community favors the artist, it could cause delays in any regulatory process if there are public hearings.

- In lieu of destruction or mutilation, consider if the art can be preserved by moving it intact, encasing it, or building around it. In one early case, a New York court held there was no destruction or alteration where a brick wall obscured an exterior mural as long as the mural remained intact.[29] VARA does not protect against obscuration.

- Although not the most honorable approach, a developer could demolish an art wall overnight, thus mooting any chance of interim injunctive relief (similar to the whitewashing in 5Pointz), but leaving the artist with a potential damage claim limited to the economic remedies specified in the Copyright Act.[30] Engaging in any demolition without a permit could, of course, run afoul of other regulations and lead to fines, and seeking a permit provides an opportunity for the artist to take quick action if placed on notice. Economic remedies for a VARA violation include actual damages (difficult to prove), the defendant’s profits (inapplicable where a work is destroyed or mutilated), or statutory damages, which can be as high as $150,000 for a willful violation. A successful VARA litigant may also apply to a court for an award of legal fees, in the court’s discretion.[31] But such sums may be a pittance to a developer of a major project and be treated as another cost of doing business. This has to be balanced against potential public and community opposition to a project.

- Building owners commissioning an artist to create a new work for a project that consists of other elements as part of a “collective” work should try to obtain a written agreement from the artist designating the work as a “work made for hire,” which makes the commissioning party both the “author” and the copyright claimant, thereby eliminating a potential future VARA claim by the artist.[32]

- If a VARA waiver agreement exists and a building owner wants to remove a covered work without destroying or damaging it, a record should be maintained and recorded with the Copyright Office of all attempts made to provide statutory notice to the artist-author.

- If a street artist of “recognized stature” (such as Banksy) paints a building wall without permission, while any copyright and VARA rights remain with the artist, the physical object on which the art was affixed—the wall itself—remains the property of the building owner. It could be argued that when the illegal art was created, an implied gift or grant was made to the property owner, who is then free to remove that section of painted wall and sell it, or put it on display, if it can be done without mutilating the art itself. Indeed, this has been attempted with Banksy pieces. [33] Here, too, there is still potential for litigation.

As is apparent, the subject of copyright and street art—legal or otherwise—is still evolving, particularly with respect to VARA claims. Newly filed and pending cases, such as 5Pointz and Katherine Craig’s Detroit mural case, will hopefully result in clearer guidance if they don’t settle before substantive rulings issue. Artists are also becoming more savvy regarding their potential rights and aggressive in enforcing them. In the interim, building owners facing issues involving street art should be cautious and consult with experts before taking any rash action.

[1] Cohen v. G&M Realty L.P., 988 F. Supp. 2d 212 (E.D.N.Y. 2013).

[2] Id. at 214, 224, 226-27.

[3] Castillo v. G&M Realty L/P., No. 15-cv-3230 (FB)(RLM) (E.D.N.Y. filed June 3, 2015). The complaint can be viewed at www.docfoc.com/castillo-et-al-v-gm-realty-lp-et-al.

[6] Craig v. Princeton Enterprises LLC, Case No. 2:2016cv10027 (E.D. Mich., filed Jan. 5, 2016). The complaint can be viewed at http://www.theatlantic.com/assets/media/files/craig_vara.pdf.

[7] http://www.crainsdetroit.com/article/20160105/NEWS/160109914/detroit-artist-sues-princeton-enterprises-over-bleeding-rainbow.

[8] 17 U.S.C. §106A(a)(3).

[9] Cohen, 988 F. Supp. 2d at 225, citing VARA’s legislative history in H.R. Rep. No. 514 at 11.

[10] 17 U.S.C. § 102(a)(5).

[11] 17 U.S.C. §§ 411(a), 412, 502, 504, 505. See also Cohen, 988 F. Supp. at 216.

[12] See 17 U.S.C. §§ 101; 201(b).

[13] 17 U.S.C. § 102(a).

[14] Id., § 101.

[15] 37 C.F.R. §202.1(a).

[16] “Copyright Office Compendium, Third Edition,” Ch. 904 (Dec. 22, 2014), http://www.copyright.gov/comp3/chapter900.html

[17] See, e.g., http://christojeanneclaude.net/projects/the-gates#.VuBhcOZvD3Y. “The Gates,” Central Park, New York City 2005.

[18] Kelley v. Chicago Park District, 635 F. 3d 290 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 132 S. Ct. 380 (2011).

[19] Id. at 304.

[20] 861 F.Supp. 303 (S.D.N.Y. 1994), aff’d in part, vacated in part, 71 F.3d 77 (2d Cir. 1995).

[21] Pollara v. Seymour, 206 F.Supp.2d 333, 336 (N.D.N.Y.2002),

[22] Scott v. Dixon, 309 F.Supp.2d 395, 406 (E.D.N.Y.2004).

[23] Cohen, 988 F. Supp. 2d at 227.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Villa v. Pearson Educ., Inc., 2003 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 24686, *7 (N.D. Ill. Dec. 8, 2003).

[27] 17 U.S.C. §113(d).

[28] Id. For details on the Visual Arts Registry, see 37 C.F.R. §201.25.

[29] English v. BFC & R East 11th Street LLC, 1997 WL 746444 (S.D.N.Y. 1997).

[30] See 17 U.S.C. §504. Penalties for criminal copyright infringement are expressly made inapplicable to VARA claims. 17 U.S.C. §506(f).

[31] 17 U.S.C. §505.

[32] See note 24 supra.

[33] See “Banksy Murals Prove To Be An Attribution Minefield,” http://www.museumethics.org/2012/02/banksy-murals-prove-to-be-an-attribution-minefield/.